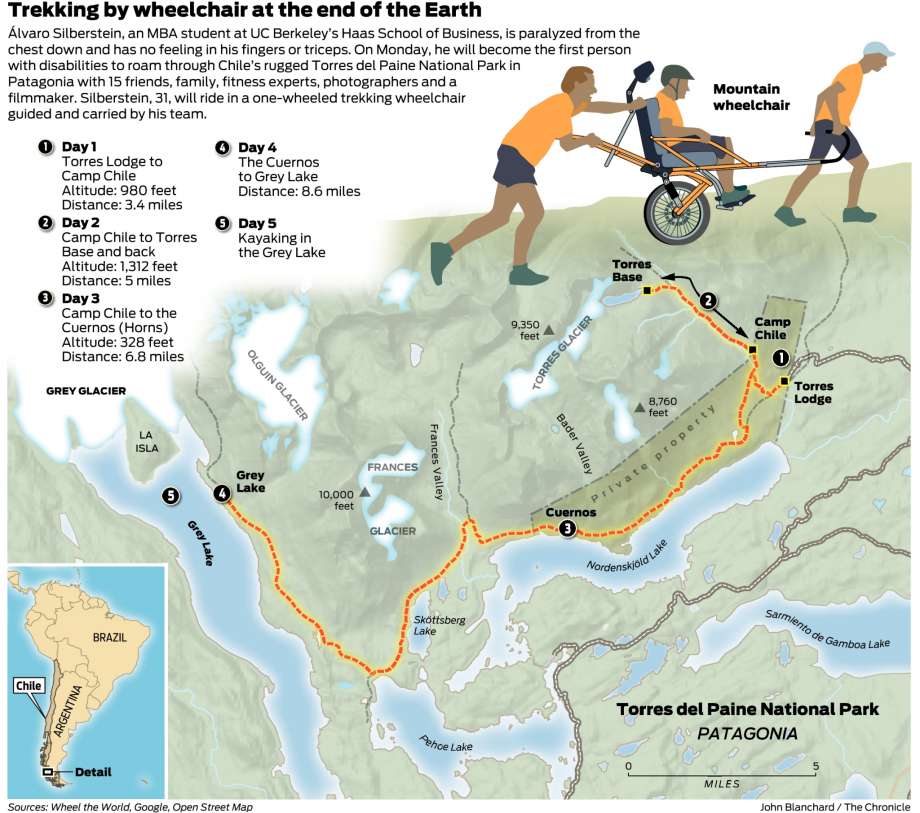

Trekking by wheelchair at the end of the Earth

Wind sweeps through southern Chile’s primeval landscape, whistling through scrub, curling around granite spires and raising waves on Grey Lake, a vast and frigid pool of melted ice. Rain soaks the region, stops, then resumes its relentless cycle.

It’s just the place for Álvaro Silberstein, a student at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business.

He’d been enjoying his life a dozen years ago as a teenager in Santiago — windsurfing, snowboarding, playing rugby — when a drunken driver wrecked his spinal cord, paralyzing him from the chest down and costing him the use of his fingers and triceps.

Waking up to that reality “was the most difficult situation in my life,” said Silberstein, 31, who uses the knuckles of his pinkies to type his papers.

On Monday, he’ll reject the physical limitations imposed upon him and become the first person with a disability to explore the unforgiving world of Torres del Paine, a national park at the southern edge of the Andes Mountains in Patagonia, where nothing but ocean separates Chile from the Antarctic ice.

Unlike national parks in the United States, no paved paths meander through Torres del Paine punctuated by wheelchair-accessible bathrooms. So the idea that Silberstein and a childhood friend, Camilo Navarro, decided on a whim in May to go there — even buying plane tickets — seemed, well, hasty.

“I said, OK, we’ll go to some places in the park that will be easy,” Silberstein recalled the other day as he sat in his wheelchair at UC Berkeley, a few feet from the compact adapter that motorizes his manual chair as needed. “But this crazy guy, Camilo, said, ‘No, dude, we’ll do everything.’”

It wasn’t hard for Navarro, 31, to pump up his friend. Silberstein kayaks in the Berkeley Marina and rides a hand-cranked bicycle. He leaped out of an airplane in Chile and went scuba diving in Australia. But after studying a map of the park’s terrain, Silberstein concluded: “This is impossible to do in a wheelchair.”

He discovered, however, that people with disabilities have done some amazing hikes. Like Kyle Maynard, born without arms or legs, who crawled to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania in 2012. And Erik Weihenmayer, a blind man, who summited Mount Everest in 2001. By 2008, Weihenmayer had climbed the highest peak on every continent — a feat known as the Seven Summits.

But the person with disabilities closest to Silberstein’s was a Canadian woman with multiple sclerosis, Pippa Blake, who was 61 in 2007 when she and her team reached Everest Base Camp at 17,598 feet after a 12-day journey in a one-wheeled, manual trekking chair.

“We said, this is the wheelchair we need,” Silberstein said. “It’s a special wheelchair designed so that other people can push (and pull) you.” It has handles in back and a harness in front so people can also hoist the chair — and its occupant — over steep, rocky terrain.

He chose a slightly different model made by a French company, Joelette, that would let him sit more vertically than Blake had. He and Navarro began to crowdfund, aiming to raise $8,000 to buy the chair, then leave it at the park for others to use.

What began as an impulse trip among a few friends soon morphed into a civil rights expedition to expand understanding of the places people with disabilities can go in the world — and a squadron of 15 people to help make it happen: friends, physical therapists, a cousin, an adaptive sports expert, photographers and a filmmaker.

“Everyone was saying, ‘I want to go!’ ‘I want to go!’” Silberstein smiled. “I couldn’t say no.”

Of course, the bigger the team, the more fresh arms will be free to carry Silberstein in the orange trekking wheelchair that, at 37 pounds, is more of a lightweight chariot. Silberstein’s training regimen included a not-entirely successful attempt to slim down. At 143 pounds, he and the chair weigh in at roughly 180.

Using it at Torres del Paine requires “a huge level of trust because he’s entirely dependent on other people for balance,” said team member Greg Milano, 47, who runs the cycling center at the Bay Area Outreach and Recreation Program in Berkeley, which adapts sports for people with disabilities. “We’ll be negotiating narrow paths on steep slopes where a fall could result in an injury. Once he’s in that chair, he’s putting all of his trust in us to make sure our footing is secure.”

Rain and strong winds, with early summer temperatures in the 50s during the day, can cause even the fittest people to slip.

So Silberstein’s physical therapist, Rachel Kahn, 26, has taken up rock climbing to improve her grip strength and balance for the trip.

“It’s an absolutely crazy adventure — but knowing Álvaro, it totally makes sense,” she said. “This isn’t just someone strolling through the park in a wheelchair. This is a really big deal. This is a crazy trip! But I have full faith.”

Silberstein will have a lot of work to do even though he won’t be pushing himself, Kahn said. As a quadriplegic with limited strength in his shoulders and arms, Silberstein has frequent neck pain, she said.

“Sitting all day puts a lot of pressure on the pelvis, and causes back and nerve pain,” said Kahn, who works with him on breathing and balancing techniques, and how to sit tall — all things he’ll especially need on the trek.

Another childhood friend going on the trip is Juan Pablo Pinto, 31, who spent three months helping his friend settle in last year at the Haas School of Business, from which Silberstein will graduate with an MBA in May.

“The group will carry him and all the extra packs. … Of course, it’s going to be hard,” Pinto said, adding that he is more excited than nervous about the five-night tent trip where temperatures will drop into the 40s, perhaps 30s, at night. The idea, he said, is to “show Chile and the world that the only barriers that exist are physical — and that everyone’s task is to knock them down.”

“Torres del Paine,” or “Blue Towers,” refers to three granite peaks that point to the sky like witches’ fingers. Silberstein and his team will cover 24 miles hiking to the towers’ base, then to a site known as the Horns, or Cuernos, and then to Grey Lake, where they will kayak on that icy pool.

Not involved in the trip is David Shurna, executive director of No Barriers USA, which he co-founded with Weihenmayer, the blind mountaineer. The Colorado nonprofit helps people with disabilities do just the kind of thing Silberstein is doing.

Juan Pablo Pinto (left) gives Álvaro Silberstein, who is paralyzed from the chest down, a hand, along with Matias Silberstein and Nico Spalloni, as Silberstein rides in a special single-wheeled wheelchair on a trek Santiago, Chile.

Juan Pablo Pinto (left) gives Álvaro Silberstein, who is paralyzed from the chest down, a hand, along with Matias Silberstein and Nico Spalloni, as Silberstein rides in a special single-wheeled wheelchair on a trek Santiago, Chile.

Although Silberstein won’t be hiking on his own, “the fact that he’s chosen to be in Torres del Paine is pretty bad-ass,” said Shurna, who has visited the place National Geographic calls “the land of the living wind,” where the right gust can tear the door off a jeep or make a bird fly backward.

“Yeah, it’s not on his own. But no one goes through tremendous adversity on their own,” he said, which is why climbers have rope teams.

Shurna pointed to the difficulties Silberstein encounters every day just to brush his teeth or take a shower. Or use his laptop. Things everyone takes for granted.

“He’s faced things that would force many of us to give up on life,” Shurna said. Instead, “what we find is that there is something powerful in the human spirit that craves adventure and wants to show the world what’s possible, and shatter expectations.”

Silberstein said it’s also about increasing accessibility for people with disabilities in his native country. He was astounded at how easy it was to get around in the United States compared with Chile.

“The (Chilean) government is aware of our trip and has been very supportive,” he said. “They’re also building a strategic plan on how to make national parks accessible. So for them, this is awesome.”

And for Silberstein, it’s just the beginning. “We realize this can be even bigger,” he said, already eyeing another expedition. He envisions taking at least four people with disabilities to the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

“Our next goal,” he said, “is Easter Island.”

Source: San Francisco Chronicle

Compartilhe

Use os ícones flutuantes na borda lateral esquerda desta página

Siga-nos!

Envolva-se em nosso conteúdo, seus comentários são bem-vindos!

Artigos relacionados

Teleton AACD. A pessoa com deficiência como protagonista.

Teleton AACD. A pessoa com deficiência como protagonista. Uma iniciativa internacional abraçada pelo SBT no Brasil.

Acessibilidade no ESG. Equipotel aborda o tema para o turismo.

Acessibilidade no ESG, para o mercado do turismo. Equipotel aborda a importância da inclusão da pessoa com deficiência.

Morte Sobre Rodas. Filme inclusivo foi candidato ao Oscar.

Morte Sobre Rodas. Dois protagonistas do filme, são pessoas com deficiência, um usuário de cadeira de rodas e outro com paralisia cerebral.

0 comentários