What’s it like to travel blind?

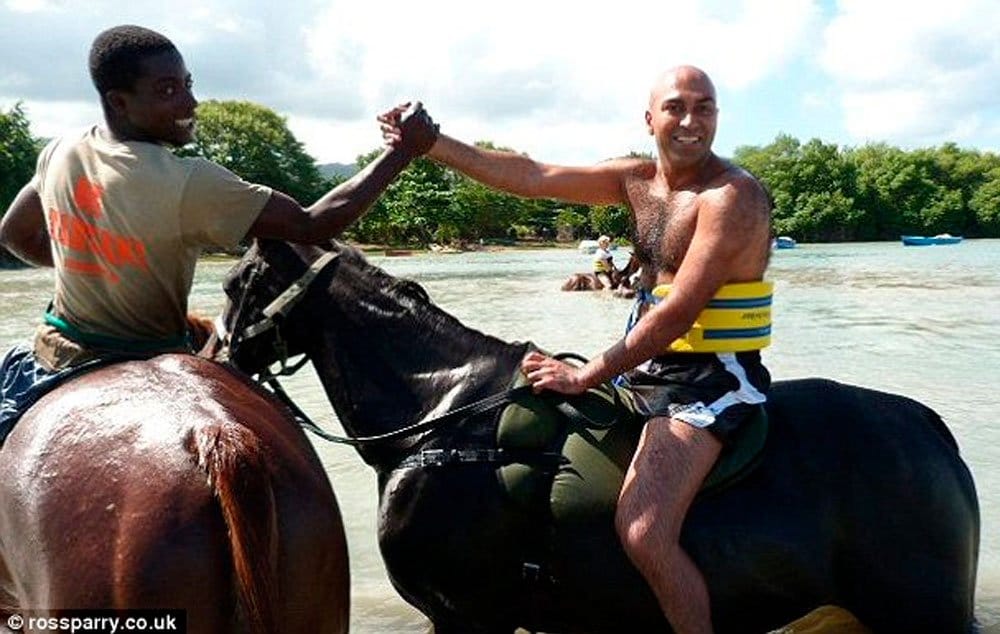

Amar Latif

Age: 37 Nationality: Scottish

I used to have my sight. I lost it at age 19. I didn’t want my blindness to hold me back. I’ve since traveled around the world, even walked 220 miles across Nicaragua.

I wish I could travel with a crane. I love architecture and I would love to be hoisted up to feel the buildings.

The thing that really frustrates me is that at airports, they often try to make me sit in a wheelchair. “My legs are just fine,” I tell them. “I just need a guide.” Maybe it has something to do with liability.

About 200 years ago, there was a book written by a blind man, James Holman, who traveled the world. One issue that hasn’t changed is the fact that people will often speak to the sighted person I’m with instead of me. The irony is that blind travelers often take the time to learn a language better to help level the playing field.

I admit that I sometimes play the blind card at airports to avoid long queues.

One thing that can make it difficult for me is hotel cleaning staff moving my things. I have a system for where everything goes – I can’t just throw stuff around like a sighted person. If a cleaner moves my shoes 10 cm (close to 4 inches), I might be looking for them for 30 minutes. So I have to find the cleaners when I arrive and ask them not to touch my things.

Blind travelers can enjoy many things just as much as sighted travelers. I make sure to plan things to activate the senses: cooking courses, concerts, and wine tasting.

It’s often nice when people forget I’m blind. I was about to skydive with an instructor in Cuba. Just before we jumped out of the plane, he said, “Don’t look down.” I said, “OK, I won’t.”

What’s it like to travel in a wheelchair?

Carl-Gustav Fresk

Age: 44 Nationality: Swedish

People are curious. I can tell that many try not to stare at me. And they get uncomfortable when they have to deal with me at the airport or at the beach. In places like India, they just go ahead and stare.

It’s hard to make the airplane weight demands. I’m dependent on some special equipment, so I’m usually 50 kg to 120 kg (about 110 to 265 pounds) over the limit. I print out a document from the International Air Transport Association website that explains my rights as a handicapped traveler – including that they’re not allowed to charge me for my special equipment. It’s always a battle, but in the end I almost never pay.

At some airport check-ins they make you check your wheelchair and use theirs. Their wheelchairs are awful – uncomfortable and difficult to move in. Some let me switch wheelchairs at the door of the plane. It seems so easy. Why can’t they all do that?

When I check into a hotel I have to see the room for myself. People will say it’s good for wheelchairs, but they have no idea. The wheelchair-accessible standards were something someone wrote on paper and the room was built by people who didn’t understand it. Like they’ll put in shag carpet or make it so I can’t get to the sink or see myself in the mirror. Often, they give me a “special room,” but that’s built for old people who want a toilet that’s extra high so they can stand up more easily. On those toilets, my feet don’t touch the floor – they just dangle uncomfortably.

People often don’t speak to me. They think that just because I’m in a wheelchair, I’m deaf.

A wheelchair creates different reactions in different countries. In Moscow, every time I went out, people gave me things. I’d go to a farmers market and people would just give me loads of food. I think they thought I was an injured soldier … and their soldiers don’t get government support.

You have to believe that most things are going to solve themselves once you get there, because many people will tell you it’s not possible.

What it’s like to travel deaf?

Helga McGilp

Age: 40 Nationality: Scottish

Deaf travelers often find people abroad far more helpful than at home! This may seem bizarre but the language barrier in foreign countries puts all travelers on a level playing field. In fact, we are better equipped to deal with communication difficulties – it’s second nature to us. We’ll happily use notebooks or gestures to convey our message in a visual manner – or even strike up a conversation.

Deaf people face many barriers in society. Many develop an inbuilt coping mechanism to handle any setbacks, which are part and parcel of everyday life. So when facing problems overseas what seems like a crisis to the typical traveler may be easier for a deaf traveler.

We often start traveling at a very young age. Many deaf people attend boarding schools and we must learn to travel to school either by air or train and do so independently. Plus, deaf social events are spread out around the United Kingdom. So we’ve become accustomed to the vagaries of travel.

Here’s one simple trick: To access information in Tibet, Mongolia and Syria, I hire a driver/guide with good written English skills.

People say English is the international language but we have something called International Sign Language, or Gestuno – a sign system that was devised using different sign languages we use at international events. So I can use this to communicate with deaf people around the world. I once had a two-hour conversation with a deaf masseur in Dali, China, who did not speak one word of English. In Santa Clara, Cuba, all the tourist information was in Spanish, but two local deaf people acted as my guides giving me more great information than the hearing tourists got.

Once, while traveling on the Trans-Siberian Express from Moscow to Irkutsk, my fellow passengers were concerned about my safety because I had my own compartment and would not be able to hear people enter at nights. I found a solution. I lodged my feet against the door while asleep so I would be alerted immediately if someone opened it.

We also experience miscommunication. In Mongolia, my driver wrote that he had to pull over to visit the “ovoo.” I figured it was the Mongolian term for “loo” and averted my eyes. The driver indicated that I should also pay a visit, but I declined. He persisted and eventually I realized that the “ovoo” was an object of cultural significance.

What’s it like to travel with a stoma?

Monty Taylor

Age: 75 Nationality: English

The best I advice I got about traveling with a colostomy bag came from my surgeon. “You just need to get on with your life,” he said. That was 13 years ago. I haven’t let it slow me down… much. I’ve since been with it around Europe, South America, North America, Africa, Asia and the Pacific.

Typically, fellow travelers never notice I have a stoma – it’s hidden by my shirt or trousers. Well, one guy noticed. I was in the sauna on a ship near Tahiti. I had a towel around my waist, but I guess there was a tiny corner of plastic sticking out. This guy asked, “Is that a colostomy bag?” “Yes,” I said. Then he told me he had been treated for cancer and very nearly ended up with a stoma himself. So the one time someone noticed, it was a nice conversation starter.

Airport security is usually not a problem. I carry an official certificate from my doctor that explains everything. Recently, though, the security guys at Heathrow (in London) did not believe me – they had never heard of a colostomy bag – and they wanted to examine me. I said, “OK, but you’ll need to have a doctor do it.” They said there wasn’t a doctor on hand and it would take a while to get one. We were late for the plane, so I just let them do the inspection. We went to a private area and I dropped my trousers. It didn’t bother me. The thing is, I happen to know the Colostomy Association offered to train security at all the airports in the United Kingdom and only one airport – not Heathrow – took them up on the offer.

Just like other travelers we can get diarrhea. And it’s just as unpleasant. That’s why I always bring plenty of extra bags… and some Immodium.

One thing that’s tricky is hot climates. It’s no problem to swim with a stoma – I do it twice a week, even sometimes in the ocean waves (the bag is tucked out of sight in my swimsuit). The water creates a strong seal. But sweating is a little more complicated. You need to wipe the area with a special barrier that prevents perspiration. It’s not enough to stop me from traveling.

One small advantage to traveling with a stoma is that it doesn’t smell if you fart. There’s a carbon filter on the bag, so you just get a small puff of nearly odor-free air.

Latif founded Traveleyes ( www.traveleyes-international.com), a travel agency that pairs blind travelers with sighted travelers and helps them see the world from one another’s perspective. Fresk has a degenerative neurological illness. At age 30, he won the open world championships in sailing, becoming the first wheelchair athlete to win against nonhandicap sailors. He represented Sweden in four paralympics games. McGilp is a health trainer with East Lancashire Deaf Society. She has been deaf since birth. She has two deaf parents and is the youngest of four deaf sisters. An avid traveler (55 countries so far), she co-runs www.deaftravel.co.uk. Taylor is a property developer and continues to travel. When he woke from surgery at age 62, the surgeon said, “Diverticulitis has caused so much damage to your colon that I could not sew the two ends together, and the stoma

Source: Charlotte Observer