For most people, these objects elicit some combination of squeamish discomfort and utmost respect. But far fewer of us connect those feelings to the untold generations of battle-scarred amputees whose sacrifices made prosthetics a public priority.

Today, double amputees regularly win gold medals at the Paralympics, and computer-based technologies allow replacement limbs to translate signals from the human brain into motion. But it’s been a long and violent haul from the wooden “peg-leg” days when amputees were pitied, ignored, or actually destined to die because of limited medical care.

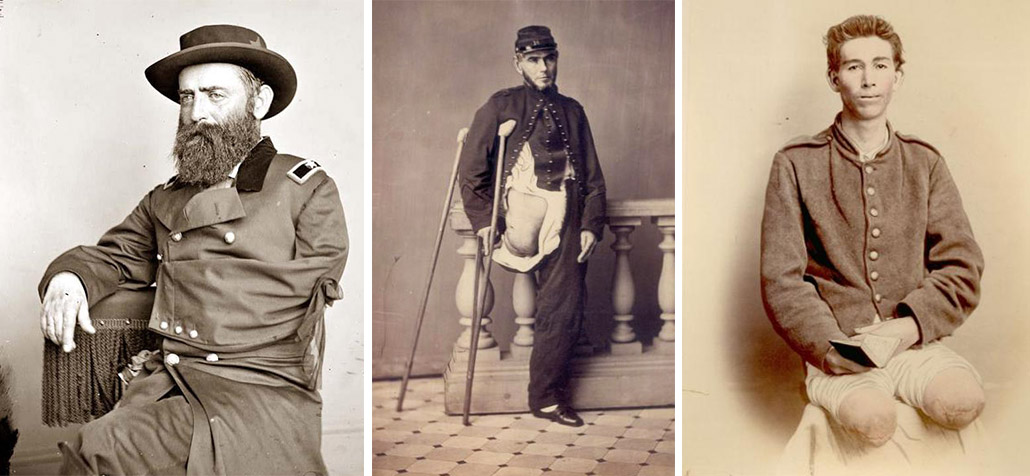

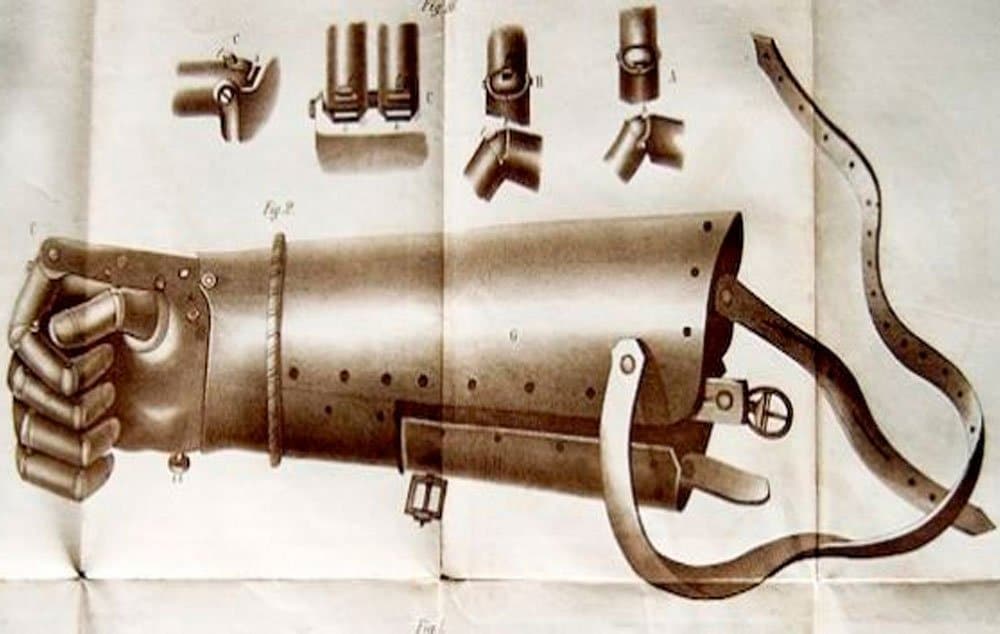

Top: Up through the 19th century, functional prosthetics were only available for wealthy patients, like this iron hand designed for the German imperial knight Gottfried von Berlichingen. Above: Three of the 35,000 Civil War veterans who survived with amputations.

Top: Up through the 19th century, functional prosthetics were only available for wealthy patients, like this iron hand designed for the German imperial knight Gottfried von Berlichingen. Above: Three of the 35,000 Civil War veterans who survived with amputations.

Though amputation was one of the first recorded surgeries, mentioned in the Hippocratic treatise “On Joints” around the 4th century BC, the procedure really became a viable option after major improvements were made in blood-loss prevention during the 15th and 16th centuries. Doctors began working with ligatures to seal off individual blood vessels and eventually used tight tourniquets around entire appendages to slow blood flow.

However, amputation was still only sought for patients whose life was already at stake due to severe infection or injury, particularly because the consequences of surgery were frequently fatal anyway. “The control of a number of associated factors–blood loss, pain, and infection prevention–has been key to greatly improving the survival chances of the amputee,” says Stewart Emmens, the curator of Community Health at the Science Museum in London. “Then, as now, the procedure was often viewed as a failure of treatment.”

Physicians like Ambroise Paré, the official barber-surgeon for the Kings of France during the 16th century, noted the unfortunate effects of prevailing surgical methods and sought better ways to heal patients. Paré was especially interested in battlefield wounds, and his first published book covered techniques to treat firearm injuries, helping to expose the problems with commonly used cauterization methods.

A selection of prosthetics from the 19th and 20th century in the archives of the Science Museum in London. Photo by Stewart Emmens; image courtesy of the Science Museum / SSPL.

A selection of prosthetics from the 19th and 20th century in the archives of the Science Museum in London. Photo by Stewart Emmens; image courtesy of the Science Museum / SSPL.

A real breakthrough in prosthetic limb mechanics came in the form of James Potts’ “Anglesey” leg design around 1800, a style popularized by the Marquess of Anglesey after he was injured in the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 . Later dubbed “the Clapper” for the clicking sound made by its articulated parts, Potts’ creation relied on cat-gut tendons to hinge at the knee and ankle, simulating a walking motion when the toe was lifted. The design was later improved by Benjamin Palmer with his so-called “American leg,” which incorporated a heel spring in 1846 and was continuously produced through World War I.

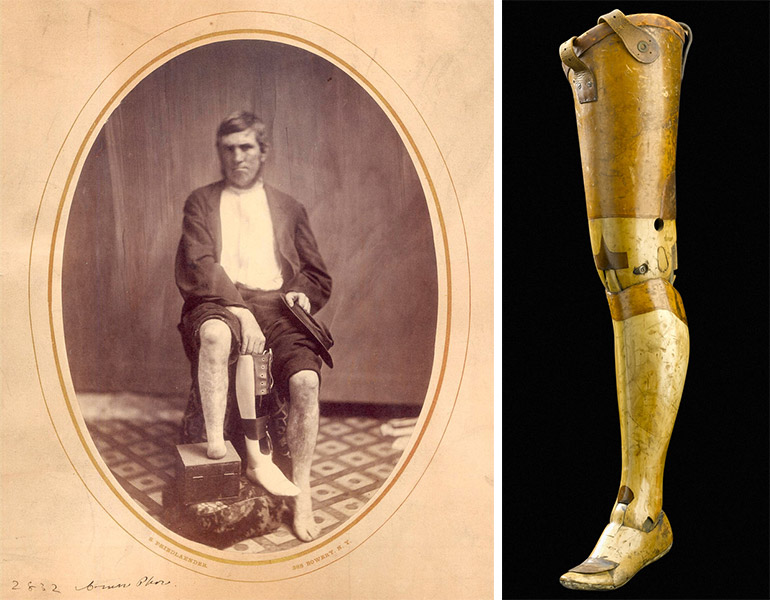

Left, this Civil War era portrait shows a veteran with a typical wood and leather prosthetic leg. Image courtesy the National Museum of Health and Medicine..b Right, this Anglesey-style wooden leg was produced in Britain around 1901, and features a jointed knee and ankle and a spring-fitted heel. Image courtesy of the Science Museum / SSPL.

Left, this Civil War era portrait shows a veteran with a typical wood and leather prosthetic leg. Image courtesy the National Museum of Health and Medicine..b Right, this Anglesey-style wooden leg was produced in Britain around 1901, and features a jointed knee and ankle and a spring-fitted heel. Image courtesy of the Science Museum / SSPL.

Whether or not they could afford a newfangled arm or leg, amputees got on with their lives, learning to cope with their disabilities and inventing their own solutions. Some became so comfortable using temporary limb replacements that they never attempted to find a fully functioning prosthetic. Others fashioned their own devices from available materials, making necessary repairs as time went on.

Left, intended as a two-week substitute, this leg was ultimately used for 40 years, requiring many home repairs by its roof-thatcher owner. Right, a father constructed this limb for his 3-year-old son in 1903, possibly from a wooden chair leg. Images courtesy of the Science Museum / SSPL.

Left, intended as a two-week substitute, this leg was ultimately used for 40 years, requiring many home repairs by its roof-thatcher owner. Right, a father constructed this limb for his 3-year-old son in 1903, possibly from a wooden chair leg. Images courtesy of the Science Museum / SSPL.

Entrepreneurs, many of them young veterans themselves, recognized the opportunity to create improved mechanical devices that would allow amputees to enjoy more normal lives.

James Edward Hanger was one of these young soldiers, an 18-year-old engineering student at Washington College who left school to join Confederate forces in a small West Virginia town. While waiting for the troops to return from a nearby village, a surprise attack by the Union army sent a cannonball ricocheting into the stable where Hanger was camped, smashing his left leg. Hours later, Hanger was discovered by the Union forces and an above-the-knee amputation was performed. The surgery became the first recorded amputation of the Civil War.

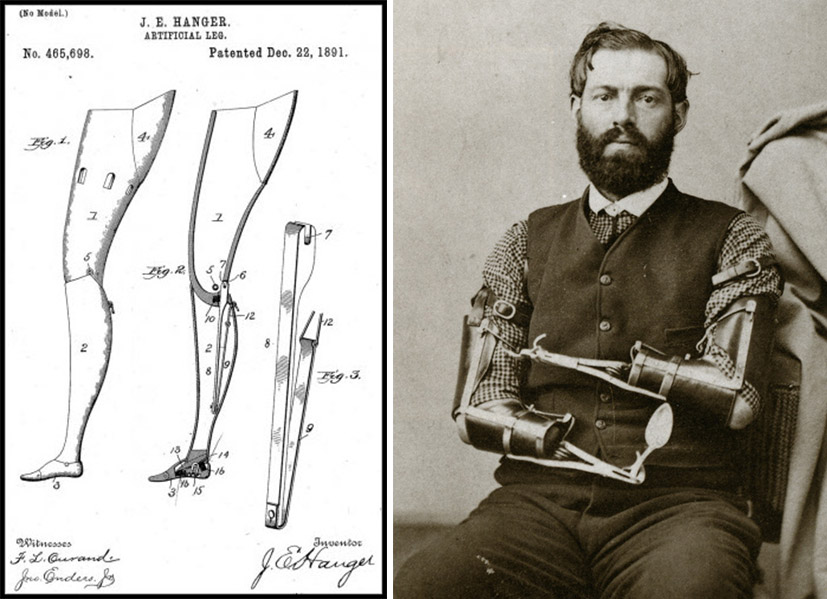

Left, one of James Hanger’s early patents from 1891 shows his novel hinged mechanism. Image courtesy Hanger.com. Right, Samuel Decker was another veteran who developed his own mechanical arms, and later went on to become an official Doorkeeper at the U.S. House of Representatives.

Left, one of James Hanger’s early patents from 1891 shows his novel hinged mechanism. Image courtesy Hanger.com. Right, Samuel Decker was another veteran who developed his own mechanical arms, and later went on to become an official Doorkeeper at the U.S. House of Representatives.

While recovering at his parents’ Virginia home, Hanger worked to improve the standard-issue replacement leg he was given by the Army, a solid piece of wood that made walking difficult and noisy. Within a few months, he created a prototype that allowed for a smoother, quieter walking motion. Though the original patent is lost, Hanger’s adjustments to the generic leg style included better hinging and flexing abilities using rust-proof levers and rubber pads.

Left, this prosthetic limb was designed for a female piano player around 1895, who went on to play London’s Royal Albert Hall in 1906 using her specially designed hand. Right, this Victorian-era arm includes beautifully detailed metalwork. Images courtesy of the Science Museum / SSPL.

Left, this prosthetic limb was designed for a female piano player around 1895, who went on to play London’s Royal Albert Hall in 1906 using her specially designed hand. Right, this Victorian-era arm includes beautifully detailed metalwork. Images courtesy of the Science Museum / SSPL.

By the end of World War 1, there were an estimated 41,000 amputees in Britain alone. Besides the overwhelming demand, shoddy fittings and unhelpful instructions meant that even available prosthetics sometimes went unused.

This prosthetic hand was designed by Thomas Openshaw around 1916 while working as a surgeon for Queen Mary’s Hospital. Two fingers of the wooden hand are reinforced with metal hooks to help with daily tasks. Image courtesy of the Science Museum / SSPL.

This prosthetic hand was designed by Thomas Openshaw around 1916 while working as a surgeon for Queen Mary’s Hospital. Two fingers of the wooden hand are reinforced with metal hooks to help with daily tasks. Image courtesy of the Science Museum / SSPL.

In a 1929 article on the evolution of the artificial limb, American doctor J. Duffy Hancock wrote that “putting a cripple back to work ranks next to saving a life.” Though harsh-sounding, Hancock’s remark captures a powerful sentiment: If we save someone’s life, they should be able to live it as fully as possible. And artificial limbs provided that key, minimizing the stigma, isolation, and lifestyle limitations that often came with amputation.

An American veteran uses an arm fitted with a welding tool adaptation at Walter Reed Army Hospital in 1919. Image courtesy the National Museum of Health and Medicine.

An American veteran uses an arm fitted with a welding tool adaptation at Walter Reed Army Hospital in 1919. Image courtesy the National Museum of Health and Medicine.

“There’s an incredible bond that takes place between a person and their prosthesis,” says Carroll. “If I’m taking that prosthetic device out of the room and bringing it back to a laboratory to check it out, they’re watching it as if it’s part of their body leaving the room. They’re watching how I pick it up, how I hold it, am I being gentle with it. And it makes you realize this is their lifeline.”

Source: Gizmodo

Enviada do meu iPad

>