Mat Fraser is standing on a stage in a hall in the Royal College of Physicians. All around him leather-bound medical tomes are locked behind bars as if they are dangerous. It’s the first performance of The Cabinet of Curiosities: How Disability Was Kept in a Box, part of a research project called Stories of a Different Kind. Over the next couple of weeks, it will tour to Embrace Arts in Leicester, the Science Museum and the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons. The project is led by the Research Centre for Museums and Galleries, which is trying to shift and inform attitudes to disability and create new narratives. Fraser has had access to artefacts and portraits across many museum collections.

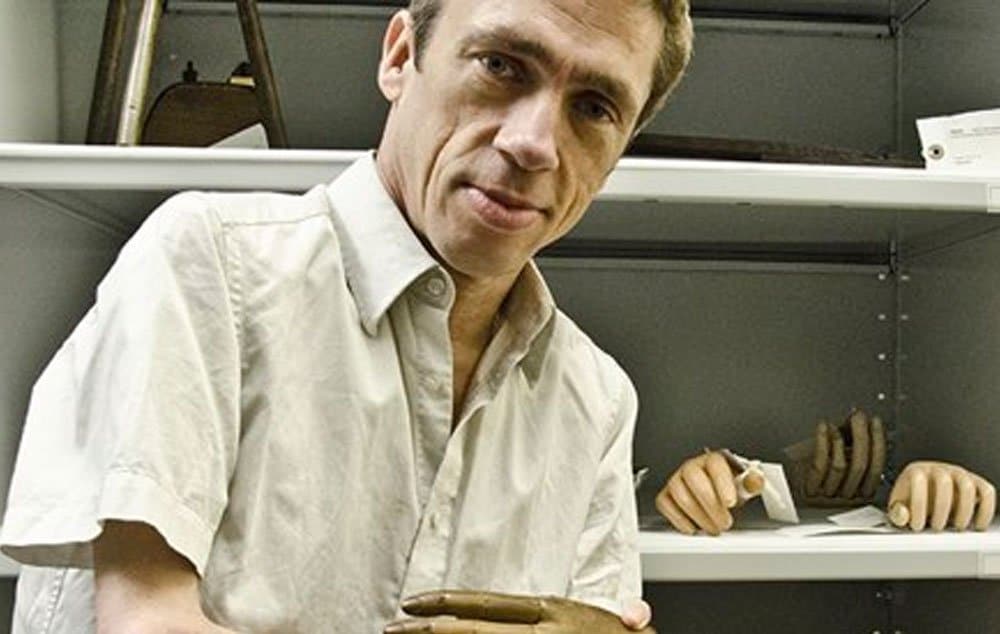

Even the presence of Mat on stage in the very heart of this citadel of the medical profession says a great deal. Like many disabled people, Mat – born with foreshortened arms after his mother was prescribed thalidomide during pregnancy – spent much of his childhood being prodded and photographed by interested doctors. Now he stands here displaying himself, and it is he who holds all the power as the performer. As in the superbly full frontal Beauty and the Beast, which toured last autumn, Fraser, in taking centre stage, is reframing the gaze of audiences. He makes us look at him and he makes us hear him, too.

He says that his initial idea when commissioned was to create a “hysterical comedy cabaret” inspired by the artefacts. But he when he saw the material, he “just didn’t find it funny”. In fact, The Cabinet of Curiosities is very funny in places, but this performance lecture is also angry at the way the medical profession has approached disability (“Curing is their job, but what if you don’t want or need to be fixed, mended or cured?”). It is equally angry at how the lives and stories of disabled people are under-represented everywhere from museum collections and everyday life to the media.

By making a spectacle of himself, Fraser is not only raising the spectre of the Victorian freak show but also subverting it by questioning what is exhibited and what isn’t, and making us confront what we are shown and what we are not shown, both in art and in life. He is helping to change the way the debate is framed: the live performance meets the dusty artefact and tries to personalise it; past meets present.

Many museums have material reflecting the lives of disabled people, but why is it so seldom displayed? Bridget Telfer, who was curator of the RCP’s Reframing Disability exhibition, which displayed – for the first time in public – some of the college’s collection of engraved portraits of disabled people dating from the 17th century onwards, has suggested that maybe there is an element of fear of causing offence or inadvertently encouraging audiences to stare in a way reminiscent of a freak show. Fraser is crossing those boundaries, smashing those sensitivities. In Cabinet of Curiosities he is telling a story of a different kind, and one that’s long overdue. It wouldn’t be doing its job if sometimes it didn’t make us feel uncomfortable. As Fraser himself says: “It’s showbusiness.”

Source: The Guardian

EU O CONHECI,QUANDO ELE VEIO NO RIO DE JANEIRO NO BAIRRO DE MADUREIRA,NO SESC.

ELES FIZERAM WORKSHOP CABARET.EU PARTICIPEI.

ELE TA NO MEU FACE.MUITO GENTE BOA.