Inclusive travel is one of those tides that washes into public consciousness each time news breaks of a voyager in a wheelchair, only to recede from collective memory when the deed is done. The challenged itinerant is left to deal with problems like fitting through a hotel room door, boarding a plane or finding a toilet. Lately, however, several initiatives have been introduced that could have the disabled out and about in greater numbers.

Varun Jain, a 29-year-old paraplegic from Rishikesh, is an inveterate traveller who launched his inclusive travel company two years ago. Travel My Way aims to reach out to wheelchair-confined travellers. “Having travelled often I recognized the need for travel companies and travel assistance providers for the differently abled,” says Jain, who set about auditing hospitality and transport providers in the hills, and listing locally available caregivers. He also sensitized taxi drivers about how to interact with travellers with special needs. A camp operator near Mussoorie went so far as to make his campsite obstacle-free for the wheelchair-bound. “They may not partake in adventure sports but they should have the opportunity to enjoy the camaraderie at a campsite,” Jain believes.

About a year before Jain floated his pennant, a socially-oriented company called Travel Another India (TAI) and a disability advocacy collective from Ladakh called PAGIR embarked on a project to make Leh wheelchair-accessible through Himalaya on Wheels. They identified monuments, hotels and lodges, assistive facilities and itineraries that catered to those in wheelchairs. “Hotel owners built larger rooms so people in wheelchairs could navigate more freely. Even the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council promised to act on our recommendations for accessible pavements,” says Gouthami founder of TAI.

Further south, in Bangalore, Vidhya Ramasubban started a taxi service called Kickstart when she realized that the unavailability of adapted vehicles could curtail the mobility of the disabled (and also the elderly and infirm). Her fleet of modified cars has front seats that swivel out and ramps. The three-month-old service currently has more pensioners as clients than people with disabilities, but she hopes that will change. “As more of the disabled get jobs in the corporate sector they’ll want to travel more,” she predicts.

However, despite best efforts, such enterprises are not making the expected numbers, even though the estimated number of people in India with disabilities is 21.9 million. Even the ministry of tourism has lately woken up to their potential to contribute to domestic tourism and has identified Accessible Tourism as a new vertical to be developed. They’ve started by issuing guidelines to make tourist facilities, hotels and monuments barrier-free, and instituted an award for the Most Barrier-Free Monument/Tourist Attraction.

The problem is that people with disabilities have little or no faith in Indian establishments going beyond the brief. “I know that in India one can’t depend on public transport. Even some hotels that claim to be accessible on sites like TripAdvisor are not really,” says Shivani Gupta, founder of the consultancy AccessAbility. Gupta, a PG in inclusive environments, is often called to weigh in on structural modifications in buildings to render them disability-compliant. “While the ministry of tourism has issued star ratings for accessible hotels, and the Archeological Survey of India has committed to making historical sites accessible, much of the change is only on paper. Moreover, a wide range of disabilities demands a wide range of adaptive interventions, which are not comprehensively made,” she points out.

Prof K Raghuraman, who teaches English at the Government Arts College in Chennai, suggests braille maps and city guides to help visually impaired people like himself find their bearings. “Muse ums should have tactile instructions navigational cards or audio guides,” he adds. “When I went to a museum in Mys ore with my parents, they were too ex hausted to explain all the exhibits to me What about guides trained in sign lan guage for the deaf-mute?”

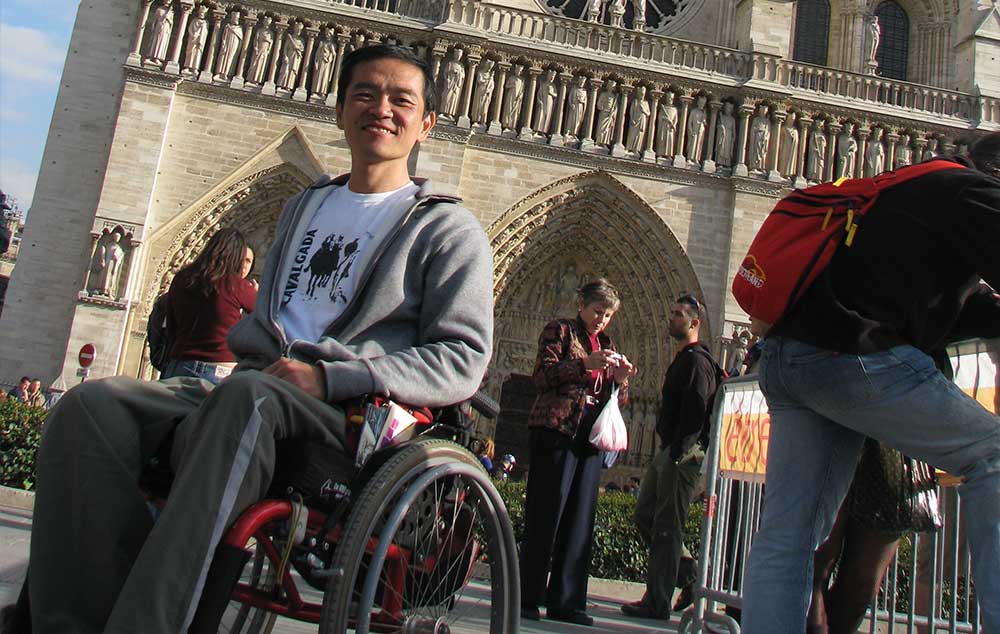

Neenu Kewlani, who has scoliosis and polio, points out that specialised travel is the prerogative of the rich, who can afford to travel by air or in their modified vehi cles and stay in pricey barrier-free rooms In 2011, Kewlani and three of her wheel chair-bound friends, Arvind Prabhoo Nishant Khade and Sunita Sancheti, set off on a 84-day tour of 28 state capitals They experienced first-hand the inadequa cies of the road and pointed these out to state governments and non-profits. “When more disabled people are visible on the streets, it will encourage others to come out too,” says Kewlani, who travelled with a portable shower chair and bedpans as public toilets make no room for wheel chairs. However, the disabled won’t ven ture out until provisions are in place to guarantee their safety and comfort away from home — an admittedly daunting task in India where in classic cart-before-horse logic, hotels want to see the numbers be fore they make structural changes.

Change will be slow in coming but it will arrive, entrepreneurs like Piya Bose are confident. The founder of Girls on The Go, a travel company exclusively for wom en, is planning to set up a travel vertical for the disabled. She’s beginning with a series of recces to holiday spots, starting with Goa (which entails identifying an accessible beach). “People need to under stand the business potential of this seg ment,” she says, “Even countries in East Asia and Africa are ahead of us in this regard.” Bose wants to eventually custom ize tours for travellers with different kinds of disabilities, no doubt the beginning of a long and promising journey.

Source: The Times of India