If everything had gone according to plan, Eileen Schofield wouldn’t have been lost after she landed at the airport in Baltimore recently.

But everything didn’t go as planned.

First, a US Airways representative refused to issue a gate pass to Hannah Newmark, a volunteer assigned to meet Schofield. So when Schofield landed at Baltimore, she wandered aimlessly around the terminal while Newmark tried to persuade the airline to give her a pass to get through TSA screening and escort her charge home.

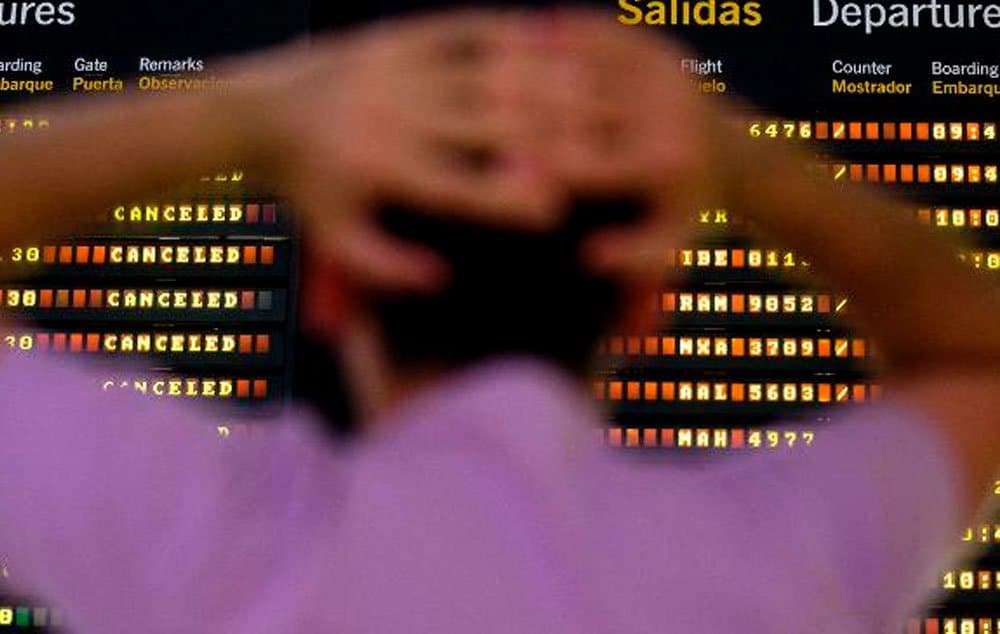

Schofield, 53, is developmentally disabled. She can’t read, write or use a phone. What happened to her sheds light on one of the least discussed air travel topics: the challenges facing passengers with developmental disabilities, and how airlines do — and sometimes don’t — accommodate them.

Charlyne Schofield, a retired federal government worker who lives in Charlotte, blames US Airways for losing her sister. For the past seven years, she’d flown Eileen from Charlotte to Baltimore on AirTran, which had always issued gate passes for her and for a volunteer on each end. But when she switched to US Airways, a representative in Baltimore told her that getting a gate pass wasn’t automatic.

“That’s what caused the problem,” Schofield says. “My sister can’t read the signs. She needs someone to meet her.”

Newmark, who works for L’Arche Greater Washington, D.C., an organization that aids the developmentally disabled, says that US Airways, which recently merged with American Airlines, was insensitive to the needs of its passenger. “I was shocked and appalled by the collective staff’s lack of understanding of the severity of the situation and help to remedy it,” she says. “I was told by multiple people that there was no chance that Eileen would get lost. But that’s exactly what happened.”

US Airways insists that it’s just following federal regulations. After Charlyne Schofield complained in writing and by phone, the airline sent her an email saying that issuing a gate pass is “at the discretion of the airlines and TSA,” adding that “passengers who are incapable of taking care of themselves in case of an emergency will not be allowed to travel on their own.”

The airline added that anyone who because of a mental disability is unable to comprehend or respond appropriately to safety instructions from its crew must travel with an assistant, implying that her sister shouldn’t have been flying without an escort.

Finding Schofield at the airport wasn’t easy. Newmark called the son of a volunteer who works at BWI and has access to the arrival area. He spotted Schofield in a different terminal, waiting patiently for her escort, and delivered her to Newmark.

Joshua Freed, an airline spokesman, says that it “generally” grants security passes in cases such as Schofield’s. “However, the final decision rests with local employees, and sometimes various considerations will cause them to decline to issue a pass,” he noted.

“We’re taking a closer look at this case and are always working to improve the experience for our disabled passengers,” he said.

Laws and reality

Accommodating the needs of developmentally disabled passengers seems to be a challenge for the domestic airline industry, even though the Air Carrier Access Act, which prohibits discrimination against air travelers with disabilities, covers mental impairments. The law defines an impairment as “any mental or psychological disorder, such as mental retardation, organic brain syndrome, emotional or mental illness, and specific learning disabilities.”

US Airways and American, for example, have a special disability assistance line. But though the US Airways website lists special procedures for a variety of disabilities, including mobility challenges and medical disabilities, it doesn’t have a section devoted to passengers with developmental needs. Some of the information can be found under “safety assistants,” and it’s almost word for word what US Airways sent to Charlyne Schofield after she complained.

Southwest Airlines, the other dominant carrier at BWI, has a more extensive list of services, but Schofield says that she’s too concerned with the airline’s open-seating policy to switch to Southwest. AirTran, her previous preferred carrier, merged with Southwest. On its site, the airline offers detailed instructions for caregivers of the developmentally disabled, including on priority boarding and special assistance. But, like US Airways, it notes, “If a customer requires personal or continuous assistance, he/she should travel with an attendant.”

A developmental disability isn’t always noticeable, which sometimes makes having an enforceable policy for passengers with special needs difficult. Passengers’ needs also sometimes conflict with an airline’s desire to make money.

Separating a family

Take what happened to Shannon Cherry on a flight from Philadelphia to Manchester, England, in 2011. Cherry, whose 6-year-old twin daughters have high-functioning autism, discovered that US Airways had separated the family in the onboard seating.

“We were shocked that an airline would separate a family with young children, regardless of disability,” says Cherry, who now lives in Walnut Creek, Calif. “What a bad situation for not only the family, but other passengers as well.”

Cherry asked US Airways to seat her family together but was told that she would have to pay extra for that. She contacted her U.S. senator at the time, Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.), whose office intervened and persuaded US Airways to allow the Cherrys to sit together on the transatlantic flight without an additional charge. US Airways would not comment on Cherry’s case because it could not find her flight records.

For some passengers, even the most accommodating policies aren’t enough to make air travel possible. Faith McKinney’s 26-year-old daughter, Camille, is among them.

“I love my child, and I want her to see the world with me,” McKinney says. But her daughter’s disability is too severe. With a cognitive age of 6 to 12 months, Camille is unable to talk and can’t tolerate the stress of air travel. The enclosed space of an aircraft would simply be too much for her to handle. McKinney, a motivational speaker based in Indianapolis, also worries about how crew members and other passengers might react to Camille’s severe disabilities. “Most people haven’t been exposed to people with special needs, especially adults with special needs,” she says.

And that pretty much sums up the problem. Because their needs aren’t always immediately visible, passengers with developmental disabilities can be marginalized, if not ignored, even when the law prohibits it. It’s a problem that’s difficult to identify, let alone fix.

But it’s not unfixable. John Cook, the executive director of L’Arche Greater Washington, D.C., believes that airlines can do better. He says that the industry’s lack of policies regarding special-needs passengers sets a “corrosive pattern of small acts of institutional denigration and discrimination that consume the time and weary the souls of people with disabilities.”

And sometimes, he says, as in the case of Eileen Schofield, it can put them in danger.

Christopher Elliott is a travel-consumer advocate and author “How to Be the World’s Smartest Traveler” (National Geographic). His columns run at seattletimes.com/travel and in print. Contact him at [email protected].

Source: The Seattle Times