Disabled Access Day: Wheelchair users share their worst accessibility stories

For able-bodied people, being able to get from A to B is an absolute given.

Whether it’s taking a train to another city, going shopping or simply leaving the house, it’s easy to take for granted the fact everything is designed first and foremost for those without a disability.

And while we should celebrate the businesses and venues that use their time and resources towards making themselves more accessible, there’s a lot of work to be done before people with a variety of conditions can lead their lives without an endless number of hurdles in the way.

‘There was a time I’d spent three days having quite grueling tests in hospital, and arrived 30 minutes before the train was set to leave – only to be told my assistance wouldn’t be coming to meet me,’ Sarah, a 30-year-old blogger and charity trustee, tells Metro.co.uk.

‘I was told I’d have to wait for the next train – if my boyfriend wasn’t with me, I know I’d have sobbed and waited but he took charge and stood up for me.’

Sarah has Ehlers Danlos Syndrome – a condition that affects connective tissue throughout the body – and so is an electric wheelchair user.

And though she says her local train station, Wellingborough, is ‘fab’ at providing access, trying to get to and from London is another story.

‘They never meet me with a ramp, and have left me waiting for up to 20 minutes before helping me exit the train,’ she says.

Which has had, as it would for anyone, a significant emotional impact.

‘It makes me feel like my time isn’t important – like they can let me wait because I’m not important.

‘I feel anxious, especially as I travel there for hospital appointments, I don’t want to be late.

‘I’ve cried, felt worthless and it’s ruined my day. It makes me not want to travel by train because it’s so much stress.’

Sarah certainly isn’t alone in her experiences with public transport.

Shona, a 19-year-old disability and lifestyle blogger, has Marfan Syndrome – a hereditary disorder of the body’s connective tissues – and so uses a power chair (an electric wheelchair) to get around.

‘Just the other day a bus driver refused to stop for me, and looked me right in the eye so that I knew he’d done it on purpose,’ she recalls.

‘There was a buggy in the wheelchair space – but instead of asking them to move, which they might have been happy to do without any issues – he left me on the pavement instead.’

‘It made me feel like a second class citizen, like able-bodied people are more worthy of respect than me.

‘It made me feel angry and frustrated that it’s 2017 and I can’t even catch a bus without something like this happening.’

‘It made me feel angry and frustrated that it’s 2017 and I can’t even catch a bus without something like this happening.’

Shona explains that while many forms of transport promise that they’ll be wheelchair accessible (think of the little wheelchair symbols displayed on the London tube map), many of them don’t deliver.

Someone far too familiar with this is 65-year-old Patricia, who has a neurological condition called syringomyelia, and so has used a wheelchair for 30 years.

When it comes to accessibility issues, she says they’ve ‘always been a problem’:

‘I was recently shopping in town with my sister – it was a pretty wet day, so we decided to catch a black cab at we came up to Glasgow Central Station,’ she says.

‘One cab driver wheeled over, took one look at me, and drove off without explanation. Another didn’t know how to use the strap in their car to secure the wheelchair in.

‘It took four or five different cabs before one took me where I wanted to go.’

Often if cabs do give a reason for not driving her, it’ll be an excuse – that ‘their ramps are broken’, or something along those lines:

‘One driver said taxis on night shifts “don’t carry straps” – as if people in wheelchairs don’t go out at night,’ she says.

‘A strange thing is that lots of them display a disabled badge in their windows, which is meant to mean they have the right training to get me from A to B, so who knows how they got them.

‘It’s discrimination.’

Patricia has made complaints to her local council, but has only received ‘short, unhelpful’ responses.

Similarly, for Shona, there’s ‘no excuse’ for failing to stop for a wheelchair user, and she believes drivers should go to more effort to move others from wheelchair spaces – even if they’re not sure it’ll be possible: ‘There needs to be better education for bus drivers, and clearer rules.’

And for Sarah, what’s necessary is an increased level of understanding.

‘Staff need better disability awareness training – they need to understand what it’s like to be in a wheelchair, and to not be able to jump off a train easily like everyone else,’ she says.

Source: Metro

Compartilhe

Use os ícones flutuantes na borda lateral esquerda desta página

Siga-nos!

Envolva-se em nosso conteúdo, seus comentários são bem-vindos!

Artigos relacionados

Acessibilidade no transporte aéreo. Atualização das regras.

Acessibilidade no transporte aéreo. Revisão da Resolução nº 280/2013 da ANAC através de consulta e audiência pública.

Inclusão no filme Wicked. Atriz cadeirante chama a atenção.

Inclusão no filme Wicked. Marissa Bode é uma atriz com deficiência na vida real, e sua deficiência não foi um impedimento para a atuação.

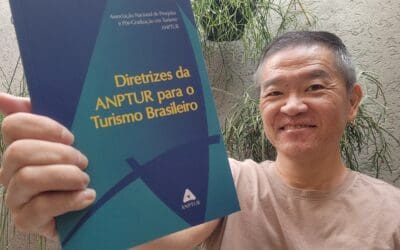

Diretrizes da ANPTUR para o Turismo Brasileiro

Diretrizes da ANPTUR para o Turismo Brasileiro. Acessibilidade é um dos capítulos desse importante guia orientador para o turismo.

0 comentários